In 2016, the San Francisco morning rush was so busy that Bay Area Rapid Transit did something unprecedented: It paid some riders cash to take the train at a different time. The six-month pilot was the transit authority’s answer to a common problem for big-city subway systems. BART could not physically run any more trains through the four-and-a-half-mile tunnel beneath the San Francisco Bay every morning; the tunnel hit capacity around 8 a.m. Maybe commuters could be induced to head downtown at 7 a.m., or 9?

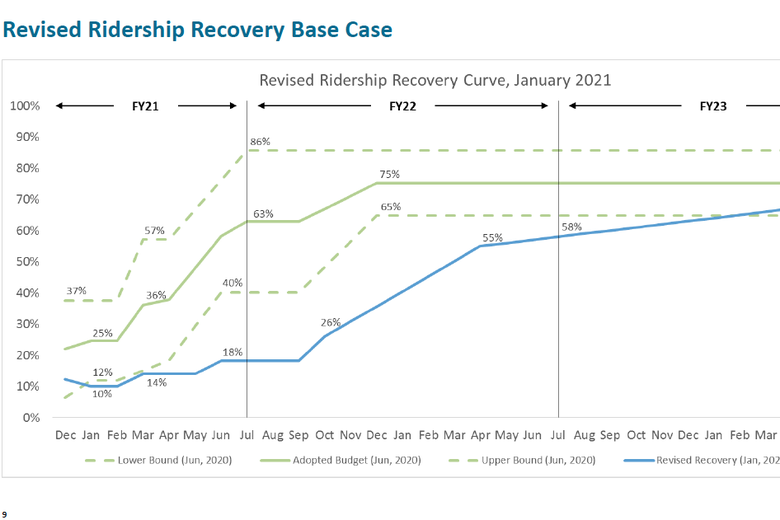

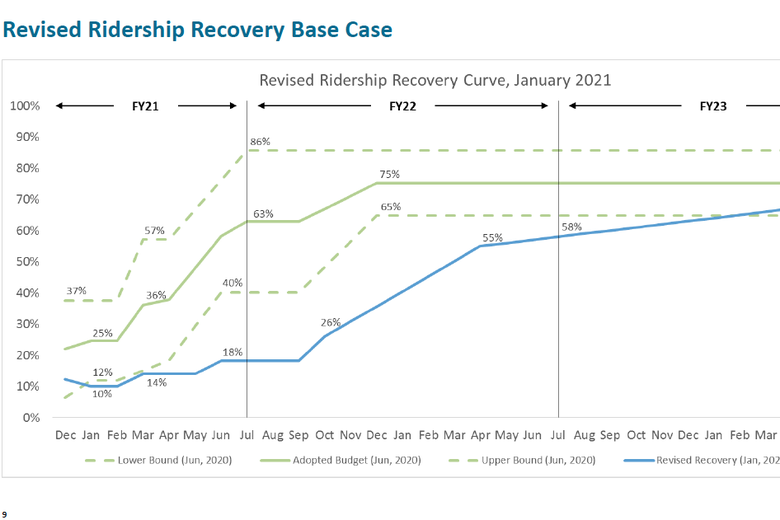

What a difference a pandemic makes. BART ridership is down about 90 percent from normal, and the future looks dimmer every day. The agency’s January 2021 ridership projection is mostly below its lower-bound projection from June 2020. “Every forecast we make that we thought was conservative, reality is much more dire than we forecast,” said Brendan Monaghan, a BART financial planning analyst.

The prevailing sense of doom comes from a dawning awareness that the old workday travel patterns are not going to snap back into place when the pandemic subsides. Even when it’s safe for Bay Area workers to travel to work, many of them won’t. The tallest building in San Francisco is the Salesforce Tower, a totem of blue glass and a symbol of the city’s tech economy since its completion in 2018. On Tuesday, the software company’s “chief people officer” outlined new work policies. “The 9-to-5 workday is dead,” he wrote. Most employees will be in the office between one and three days a week. Twitter, another San Francisco tech employer, has announced an indefinite work-from-home policy. The situation looks similar in New York, D.C., Chicago, and other major U.S. cities.

Last month, the transportation scholar David Levinson asked: What if downtowns never come back? In Sydney, where Levinson teaches, the virus is contained. Car traffic has returned to normal, but transit use is down about 40 percent from last year. “Transit demand may be off more than 80% since now parking is easy, and there isn’t enough demand from non-work trips to compensate,” he wrote, concluding that the central business district “has peaked in significance. The consequences will be felt for the rest of our careers.”

If it does come to pass, the decline of downtown would have severe ramifications for American life, upending local businesses, municipal budgets, housing markets, and civic culture. But mass transit would grapple with its effects first. Asking a transit agency to operate without rush hour is like asking a restaurant to operate without dinner service. Most systems are built to serve a downtown core and managed to serve peak demand. And it was during that peak that transit agencies collected most of their fares.

Fewer people traveling isn’t a problem in and of itself—until the resulting loss of revenue produces a death spiral of service cuts and ridership drops, leaving some riders in the lurch and forcing the rest of them to buy cars. An unfortunate irony of American transit is that the best systems are also the ones most dependent on revenue from riders. “Farebox reliance was for a long time a point of pride,” said Monaghan at BART. “But it turns out to be an unmitigated risk.” At Metra, the Chicago-area commuter rail network, high-quality, crowded, peak service subsidizes mediocre off-peak service, said Metra CEO Jim Derwinski. “You’re filling those trains up, and those rides are paying for the trains that are off-peak that aren’t full.”

Rush-hour travel to a concentrated area is also the scenario in which transit best rivals driving on cost and convenience, thanks to jam-packed roads and expensive parking rates, said Katie Chalmers, who supervises route planning at King County Metro in Seattle. “Transit is often more time-competitive during peak periods,” she wrote in an email. “Transit really excels in moving large groups of people to the same place and at the same time.”

And yet when I asked her and other transit professionals about the importance of peak-hour ridership, they all said more or less the same thing: Peak-hour transit is a blessing and a curse.

Picture a 10-lane road with sparse traffic, said Zakhary Mallett, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Southern California who studies peak-hour transit. Just as roads are built to accommodate maximum rush-hour traffic and then spend many hours looking overbuilt, so transit has become bloated to meet peak demand. “We build a ton of capacity and buy a ton of vehicles for the peak of the peak,” he said. “Peak service is extremely expensive when you consider capital costs. My hypothesis is that peak period travel, after you account for capital costs, is more expensive than off-peak—even after accounting for revenues.”

Translation: We have spent a ton of money to prepare subways and buses for morning rush hour. Even with all the crowded platforms, it’s not clear if it pays off.

One example is train cars. Mallett says 41 percent of BART’s train cars are bought and maintained just for the peak of the peak. Alon Levy, a Berlin-based transit analyst, calculates that rush-hour trains cost as much as five times more as those used for off-peak service per mile of use.

Unfortunately, it’s hard to downsize on a dime. The resale market for trains is not good, and there’s no undoing peak-oriented capital projects like New York City’s East Side Access, the “most expensive mile of subway track on Earth” that will give suburbanites better access to Manhattan’s Grand Central Terminal.

But some peak-hour expenses could be wound down, such as labor inefficiency. “When you see a full bus or train running one direction [at rush-hour], I always picture it half-empty,” said Jarrett Walker, a transit planner in Portland, Oregon, because it must be run back with no passengers. For employees, peak shifts are short. They drag operators into the city center. Even if you’d like to leave the vehicles there for the afternoon rush, you’ve got to get the workers back to where they came from.

As it happens, the pandemic reckoning over rush-hour transit neatly aligns with a broader critique that has been underway for a decade. What if off-peak, non-downtown ridership is low because off-peak, non-downtown service is bad? “There’s compelling case there’s a lot of travel demand outside of peak not met by current service patterns, and changing to a service model that offers consistent, all-day frequency could end up capturing trips and having positive revenue effects,” argued Ben Fried at Transit Center, a think tank in New York.

Off-peak travel outside of downtowns has been surging for decades. Transit systems have rarely been there to meet the demand, however. In fact, many of them—such as Washington, D.C.’s WMATA and New York’s MTA—have moved in the opposite direction, forcing late-shift commuters to blow their paychecks on Uber rides because the trains now stop running earlier. In New York City, the situation is particularly absurd, since empty trains are still moving underground all night—the agency just isn’t letting the late-shift workforce ride on them.

In 2018, New York City Comptroller Scott Stringer published a report on the MTA’s failure to adjust service to meet the needs of musicians, actors, nurses, home health aides, delivery workers, bartenders, baristas, and other workers unlikely to fit into the typical commuting pattern. Ridership into Manhattan before 7 a.m. grew twice as fast as ridership after 7 a.m.; subway service did not keep pace. “Traditional commuters” made up barely more than half of MTA traffic, down from 61 percent in 1990. And the decline of the classic peak trip was both temporal and spatial: The fastest-growing group of New York City commutes by far came from workers who didn’t go to Manhattan at all, but instead commuted between boroughs or adjacent counties.

But instead of reviving train service on an underused right-of-way connecting Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx, New York’s politicians and planners have poured their energy (and an astonishing amount of money) into four new, multi-billion-dollar transit hubs serving the two Manhattan business districts.

Not surprisingly, catering to peak commuters means tailoring transit toward the needs of a whiter, wealthier, and more male cohort than straphangers at large. In the 2018 study of New York, the rush-hour commuter group was 52 percent college-educated with a median income of $42,300. The before-sunrise crowd, by contrast, was 31 percent college-educated with a median income of $35,000. The second group also featured more foreign-born workers and more minorities

This pattern holds up across every city. Even including off-hour workers, commuting in general accounts for only three in 10 transit trips, according to the National Household Travel Survey. Equity advocates say the 9-to-5 bias isn’t just unfair; it also depresses ridership by dissuading riders who travel for reasons besides work. This is a major issue for woman travelers, whose trips—particularly for childcare or family responsibilities—are more likely to be off-peak.

This is not by accident; the downtown, peak-hour emphasis hinges in part on the received wisdom that transit users are either “captive” or “choice” riders, and that better service is necessary to keep “choice” riders (with cars, jobs, and cab fare) on board. In reality, as the transit analyst Uday Schultz reminded me, off-peak riders are more likely to bail when service gets worse. This has been borne out over the past decade, as bus riders have fled transit in response to U.S. cities’ inability (or lack of desire) to rise to global transit standards and liberate buses from traffic with dedicated streets or lanes.

During the pandemic, cities such as Boston, New York, San Francisco, and Chicago have seen ridership remain higher in neighborhoods with more essential workers. And agencies are (finally!) changing service to respond: In San Francisco, Muni chief Jeffrey Tumlin has consolidated a diminished pandemic-era network around good service in high-ridership areas. In Boston, with commuter trains registering just 7 percent of their pre-pandemic rush-hour ridership, the schedule has shifted to provide 30-minute service all day to Chelsea and Lynn, two cities north of Boston with large Latino populations.

Even Chicago’s Metra, despite its reliance on peak-hour fares, will experiment with more frequent, all-day service. “This is the time to try new stuff,” Derwinski told me. “This is the time to lay out a different service model. It’s not just the core 9-to-5 worker, it’s the folks using Metra to go to the doctor or to a sporting event.” Derwinski cited a prior service increase at Hyde Park, the neighborhood eight miles south of the Loop that includes the University of Chicago. The introduction of 20-minute service, he said, helped make Hyde Park “our heaviest station outside of downtown.”

Unfortunately, many cities have spent billions to reinforce transit’s rush-hour, downtown functionality—and many of those costs are sunk. Downtown business interests and long-haul office commuters have been powerful advocates in getting public money committed to new projects. How much effort will be spent to recover rush-hour riders after the pandemic instead of experimenting to pull in, for example, teenagers or seniors or grocery shoppers or other underserved groups? Does the transit coalition stay intact when the raison d’être is ensuring mobility without cars in general and on a regional scale, rather than specifically reinforcing the centrality and viability of downtown?

Walker, the planner in Portland, recently redesigned the bus network in Houston to be less focused on downtown. He said he believes there are a lot of potential transit riders out there who are not getting picked up. “We’re leaving a lot of low-income ridership on the table,” he told me. “And a lot of zero-car ridership on the table. We don’t need luxury, we just need usefulness.”

In the long run, Walker said, moving away from the twin camel humps of the morning and evening rush would be a great thing for transit operators who have historically shelled out for both capital and operating expenses to meet peak demand. The demand curve is flatter in Paris, for example, where a focus on all-day use (and concurrent investment) has taken ridership up by 20 percent in the last two decades. Less Métro, boulot, dodo (subway, work, sleep) than Métro, bus, Métro. American politicians, by contrast, have neglected the suite of transit, traffic, parking, and land-use policies that might make transit useful for anything beyond traveling to and from the downtown core at the busiest times of day.

If those trips vanish, urban transit will have a short window to reinvent itself. The pandemic may be a chance to reset. It may also be an ultimatum.

"Hour" - Google News

February 11, 2021 at 05:45PM

https://ift.tt/3tKUO69

If Rush Hour Dies, Does Mass Transit Die With It? - Slate

"Hour" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2WcHWWo

https://ift.tt/2Stbv5k

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "If Rush Hour Dies, Does Mass Transit Die With It? - Slate"

Post a Comment